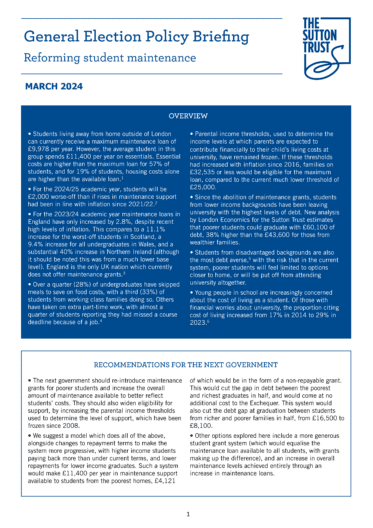

This General Election policy briefing, the third in our new series of briefings ahead of the next election, looks at the student maintenance system, which determines the amount of money students have available for day-to-day living costs throughout university.

While the tuition fee system has received much political and media attention in the last two decades, far less attention has been paid to student maintenance. But for many students, this funding is of more immediate importance, and can have a major impact on whether they can afford to move away from home, how much paid work they need to undertake during their studies, and even whether they can afford to go to university at all.

The abolition of maintenance grants – which did not have to be paid back – in 2016 also means the student maintenance system puts the highest debt burden on students from the poorest families, and rather than a system which enables young people from all backgrounds to attend and thrive in higher education, it impacts on the university choices of some, and for others whether they attend university at all.

With the cost of living crisis exacerbating these challenges, this briefing illustrates why student maintenance is an issue which needs to move up the political agenda ahead of the election.