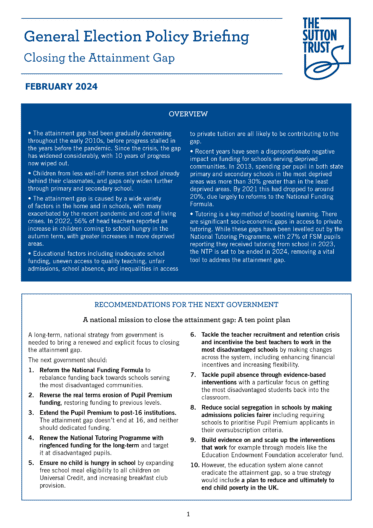

This General Election policy briefing, the second in our new series of briefings ahead of the upcoming election, looks at the attainment gap – the gap in educational outcomes between students from more and less affluent backgrounds.

During the early 2010s, the gap across all school stages had been narrowing gradually. However, this progress stalled in 2017, before the pandemic altered the landscape considerably. Since 2020, the attainment gap has widened notably, with 10 years of progress in closing the gap wiped out in just a few years.

While there has been broad support across the political spectrum for efforts to reduce the gap, it has not been a major issue in political debate. But the issue is a ticking time bomb for future social mobility.

This briefing outlines existing evidence on the attainment gap, including how it is measured, how it has changed over time, as well as the long-term impacts for both individuals and the wider economy. It also examines the underlying factors preventing lower income young people from meeting their potential, with recommendations on what the next government can do to work towards closing the gap for good.