Opinion

Our Opportunity Index provides an in-depth analysis of how socio-economic background, geography and opportunity interact, including how progression to higher education varies for pupils across the country. Erica Holt-White, our Research and Policy Manager and one of the authors of the report, explores some of the differences in access to university using the regional and constituency-level data in the report.

A university degree is one of the surest routes to social mobility. Indeed, our previous research has found disadvantaged young people are four times more likely to become socially mobile if they attend university. But this group are still the least likely to attend in the first place.

Access to university has not yet had a great deal of attention from the new Government. But given its importance as a route to social mobility, it should be considered a key part of the Government’s Opportunity Mission – a mission which aims to break down barriers and tackle inequalities in life chances.

The mission is certainly welcome, but to achieve success, it is more important than ever to understand how exactly opportunities diverge, and how to tackle such inequalities so that every young person, no matter what family they come from or where they grew up, has an equal chance to succeed.

The Sutton Trust’s new Opportunity Index, and accompanying research, shows that there is a long way to go.

The Opportunity Index uses data linkages from the National Pupil Database (NPD) and the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO), covering more than 10 million young people across the past 25 years, to provide an unprecedented insight into the geography of opportunity and social mobility in England.

Constituencies have been ranked by their index score, which has been calculated based on six key indicators of opportunity for Free School Meal (FSM) eligible pupils who grew up in the area. The results are stark: the top 20 constituencies on our Opportunity Index are all in London, whereas no London areas even fall into the lowest ranked 200 constituencies.

Access to university is a key element of the Index, which considers the proportion of FSM students from a constituency who go on to achieve an undergraduate degree by age 22.

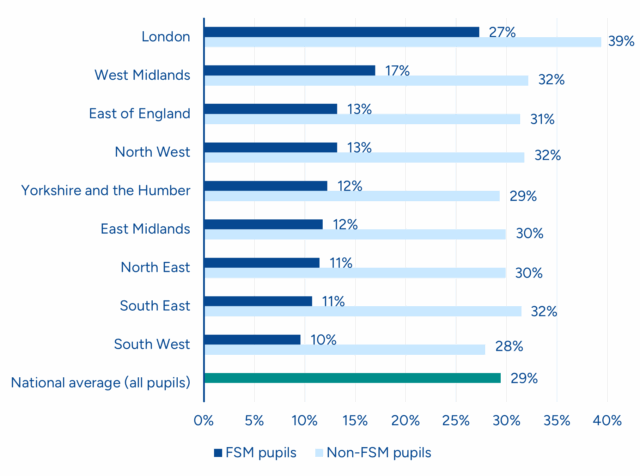

Whilst 29% of all pupils in our data went on to get a degree by age 22, just over 1 in 4 (or 27% of) FSM pupils from London did so – not too dissimilar to national average for all pupils. But the chart below shows, only 1 in 10 FSM pupils from the South West have a degree by age 22 (making it the region with the lowest figure). The gap in university attendance between FSM and non-FSM pupils was largest in the South East at 21 percentage points (11% vs 32% respectively) and smallest in London at 12 percentage points (27% vs 39%).

Figure 5: Percentage of FSM and non-FSM pupils with an undergraduate degree by age 22, by region

When we look at this data by constituency, similarly to our overall Opportunity Index, all bar one of the top 20 ranked constituencies for FSM pupils on this measure were in London; the exception being Birmingham Perry Barr (32% of FSM pupils had a degree by age 22). In fact, only seven of the top 50 are outside of London. Although we cannot assume that the pupils from these constituencies went to universities in the same area, or even region, it is interesting to consider what our previous research has shown about London universities and social mobility.

Many of the top ranking institutions for social mobility are less selective universities located in London, combining high access rates with good earnings outcomes. This is likely due to the higher salaries on offer for graduates in London, as well as the relatively high rates of disadvantaged pupils with high levels of attainment, along with the ethnic mix.

15 of the lowest ranked 20 constituencies were in the South West or South East of England. In all 20 constituencies, the proportion of FSM pupils with a degree was at least 23 percentage points lower than the national average for all pupils.

What does this mean for opportunity?

From our own previous research, we know how attending university can be such a vital step towards social mobility. But yet, as our new research shows, a FSM pupil in one part of the country (Stratford and Bow) is over 10 times more likely to attend university than someone in another (Bristol North West), by no fault of their own. How is this fair?

Over the past 25 years, some progress in university access has certainly been made, which we are proud to be involved with through our programmes, who reach over 8,000 students per year. But even still, access gaps have remained and improvement on fair access to the most selective institutions in particular has been slow. There is still a distance to travel.

The higher education sector is facing substantial financial difficulties, with many institutions having to consider expenditure on access initiatives, including pulling back on particular programmes and partnerships. But widening participation must not be forgotten.

The government should redouble efforts on access, with a strong focus on socio-economic disadvantage. Renewed efforts should include stronger regulatory expectations including the use of targets, and making a greater range of levers available to the Office for Students (OfS) to act where universities are not making sufficient progress. Maintenance support should also be set at an appropriate level so that no young person is unable to head to university or limited in their higher education options because of the cost.

Usage of contextual admissions – where the background of a university applicant is taken into account as part of the admissions process – should also increase amongst all universities. This is a crucial tool for widening access to higher education and, ideally, a sector-wide approach could be transformational.

If the government is truly serious in its aims to break down barriers to opportunity, significant investment in the education system is required. Improving access to university for disadvantaged young people, particularly those in the ‘left behind’ parts of the country, must be seen as a priority. Otherwise, not only will the government’s mission fail, the life chances of so many of the next generation will be severely limited.

Visit our interactive map to explore the key findings.