Press Releases

Our Senior Research & Policy Manager, Rebecca Montacute, uses the findings from our research on tutoring to assess the impact of the National Tutoring Programme and what the future of the programme is.

Paying for private tuition on top of a child’s standard schooling is growing increasingly popular. But its use is creating a two-tier system, with wealthier families able to secure their children advantages that poorer families simply cannot afford.

These disparities are particularly jarring given the extensive evidence that tuition could be a powerful tool to help close the attainment gap between poorer children and their better off peers. Before the pandemic, schools, charities and tutoring organisations had made efforts to expand provision to disadvantaged young people, but these are limited in scope, with no national plan to increase access.

The tutoring landscape completely changed with the pandemic and the subsequent creation of the National Tutoring Programme (NTP). The government initiative was the first national programme to widen accessibility to tutoring, designed to help students to catch up on lost learning – particularly the poorest young people, who had been the most heavily impacted by pandemic related school closures.

Three years since the start of the crisis, our new report looks at whether the NTP has succeeded in widening access to tutoring, and what can be done in future to help it reach the poorest students.

Balancing quality and scale

Setting the NTP up at speed during the pandemic, while attempting to provide tuition both at scale and at high quality (given the widespread and urgent need for help), has led to major issues in delivery, with the programme having a considerable amount of criticism.

The first year of the programme (run by the Education Endowment Foundation and Teach First) had a higher focus on quality and wider development of the tuition market, with tutoring provided by external organisations whose quality had been checked by the NTP (the Tuition Partners arm of the NTP), or by staff recruited and trained by Teach First and embedded into schools (Academic Mentors). But it did not deliver tutoring at the scale required by the impacts of the pandemic, with only 250,000 courses started.

But while the second year (run by Dutch multinational Randstad) reached a much larger number of pupils, it did so by moving to a model of largely school-led tutoring (rather than tutoring provided by accredited external organisations). Over 2 million courses were delivered in the second year of the NTP, 81% of which were school-led.

The quality of provision since the pivot to school-led tutoring remains largely unclear (an upcoming assessment of the second year of the NTP will look at this issue in detail), but there are some worrying warning signs. A recent evaluation by Ofsted in 63 schools found that while tutoring was strong in over half the schools they visited, in a sizable proportion (10 of the 63) tutoring was haphazard and poorly planned. But tutoring being school-led will not in and of itself ensure high quality, and the system needs to be adapted to develop and then encourage best practice.

While in the midst of the pandemic, a focus on speed and scale was understandable, as we move forward, it is crucial the NTP re-focuses on quality of provision. Delivering tutoring directly within schools has the potential to be hugely successful if done well, with links to the curriculum and good relationships and planning between tutors and teachers. But tutoring must also be genuinely additive, with funds not simply propping up existing school support (for example, using them to pay for teaching assistants).

There should be greater accountability of tutoring to Ofsted, . particularly in terms of the quality of tuition being offered.

Getting tuition to disadvantaged students

The NTP has also faced challenges on whether it has done enough to reach disadvantaged pupils. The initially stated purpose of the programme was to reach this group, but Year 1 had no explicit targeting, and the initial target set in Year 2 was subsequently dropped, with both years criticised for a lack of reach. Just 47% of those reached by the NTP in both Year 1 and Year 2 were disadvantaged.

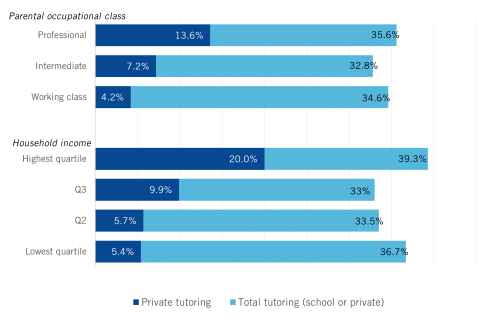

But despite these challenges, there is evidence that school provided tuition (much of which is likely to have been from the National Tutoring Programme) is helping to level the playing field when it comes to access. Data from the COVID Social Mobility and Opportunities (COSMO) Study, a major new longitudinal study looking at young people who were in Year 11 in 2020/21, shows that while private tuition is heavily skewed to better off students (as measured by either parental occupation or household income), tutoring from schools has helped to even out access to provision.

Figure 1: Patterns of private tutoring and total tutoring (school or private) during Year 11

But more could still be done, COSMO data also shows that about 60% of FSM-eligible pupils have not received tutoring, and more than half of pupils who feel they have fallen behind their classmates have not done so.

Going forward, both to continue to aid with catch-up efforts, and to tackle the longstanding attainment gap, the NTP should be refocused towards disadvantaged students, with stricter targets and incentives for uptake among disadvantaged pupils.

Expanding the tutoring market

School-led tutoring may not be the right fit for all schools, and external organisations such as the Tutor Trust and Action Tutoring have had over a decade of successful delivery, bringing external expertise on tutoring into schools and working successfully alongside school staff, which have been welcomed by many schools who have used them.

But these organisations are not evenly spread across the country, particularly outside the South East, and work is still needed to to help to expand the highest quality provision across the country. However, the latest contract for the NTP does not include provision to actively grow the tutoring market. The Tuition Partners arm of the NTP should be fully re-established to improve provision in the tuition market long term.

Continuing government subsidies

The government plans to reduce the subsidy for the NTP next year to just 25% of the cost of tuition, down from 60% this year. This is a huge point of risk for the NTP, after negative media attention during the first rocky pandemic delivery years, and the danger that even schools with positive experiences of the programme may not continue to use it given other funding pressures. Indeed, a recent survey found one third of head teachers say they are likely to cut the number of children receiving tutoring next year due to wider funding concerns.

The government should postpone cuts to the subsidy, to give schools longer to recover from the pandemic, and the NTP longer to establish itself in the school system. Longer term, government should look at additional funding for tutoring, or ways to incentivise schools to use pupil premium funding to cover the cost of high-quality tuition.

Going forwards

Catch-up support is still needed by many students, but we now have a chance to fully reflect on the National Tutoring Programme, both to improve it for those students, and to think seriously about the programme’s future.

It is vital that challenges in implementation during the pandemic do not derail the need for a national programme for tuition in schools long term. We simply can’t afford a return to the pre-COVID status quo where tutoring was largely the preserve of families with the most financial resources.