Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to bring about transformative change in practically every sector, including in the education system. In schools, we are just starting to see its impact, with AI tools already saving teachers time in tasks like planning and marking, as well as wider staff time spent on administrative tasks. In the long term, AI could fundamentally change how education is delivered.

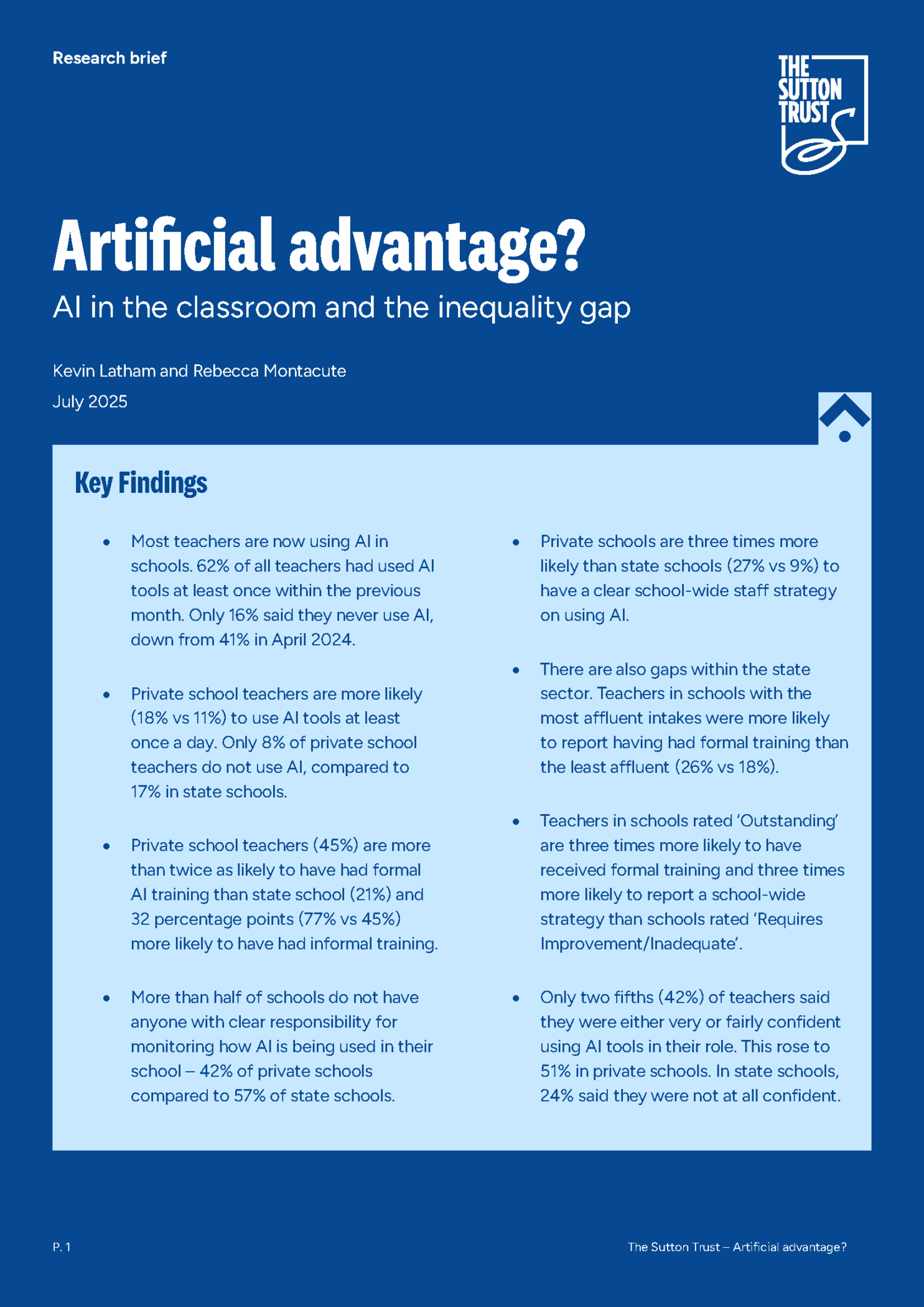

But the emergence of this technology also brings considerable challenges to education. While some of these have received lots of attention, such as the impact of AI on pupils’ critical thinking skills and their ability to problem solve, others are yet to be explored in great detail. This report looks to open up one area of debate regarding AI in education left relatively unexplored to date: socio-economic disadvantage.

As AI transforms the education sector, what will it do to the existing structural inequalities in the system? How will its impact be felt by different groups of students, and particularly those from lower income homes? Will the upheavals brought by AI in the education system be positive for those who are not currently served well by the status quo, or could they potentially deepen existing disadvantages?

This research explores how AI is being used in schools today, and whether inequalities in access are already starting to emerge. It looks at the barriers teachers face in making the most of the technology, and how that differs by both school type and the level of deprivation of students the school serves.