Press Releases

The Sutton Trust has been looking closely at the issue of food poverty among children for a number of years. In light of new data from the Trussell Trust, our Senior Digital Communications Officer, Lewis Tibbs, reiterates the urgent need to tackle this growing issue.

More than 1.8 million emergency food parcels were provided to families with children across the UK between April 2024 and March 2025.

I had to read the Trussell Trust’s latest figures several times before they really began to sink in.

But somehow it gets even more worrying upon a closer look. The figure mentioned represents a 46% increase in the number of food parcels provided compared to five years ago, and there has been a 32% rise in parcels distributed to families with children under the age of five. And this is just the Trussell community food banks – there are many more charities working to provide food for those in need.

It’s hard to find the words to truly articulate the severity and scale of this situation.

What is clear, though, is that many children today will be navigating their way through their education while living in food poverty. There are pupils across the country who are going into school hungry, trying to learn on an empty stomach, perhaps unsure whether they will have a warm and nutritious meal to eat in the evening.

Hunger in the classroom

Combating child food poverty – and its root cause, poverty more broadly – is important for several reasons.

The first is a more intuitive, moral one: no child should be going hungry in the UK. It is unacceptable that children in a nation as wealthy as ours are missing out on something as foundational as adequate nutrition.

Beyond that, child poverty is a major driver of learning outcomes. Hungry pupils find it harder to concentrate and engage in the classroom. They are more likely to be absent from school, and they are more likely to engage in disruptive behaviour.

Because of this, the Sutton Trust has been paying attention to growing food insecurity and rising levels of poverty among children for a number of years.

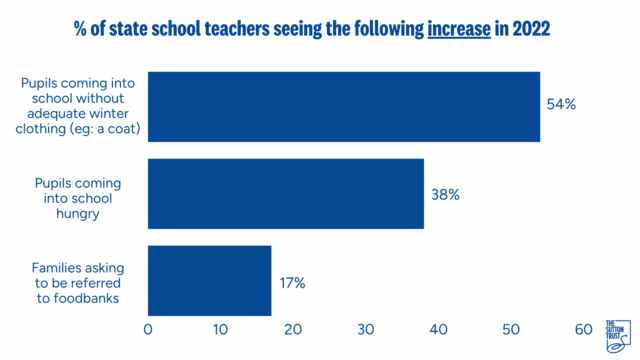

In late 2022, our polling revealed that 38% of teachers reported seeing an increasing number of pupils coming into school hungry, with 17% saying they had seen an increase in families asking for foodbank referrals.

Additionally, our research as part of the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunity (COSMO) Study identified a concerning link between food poverty and lower GCSE grades.

The importance of good nutrition for children’s health, education and overall development can’t be overstated. This is why the Trussell Trust’s data on the number of food parcels provided to families with children under five is particularly unsettling.

The first five years of a child’s life are crucial, so food poverty can be particularly damaging during this time. The Education Policy Institute recently reported that food poverty experienced by under-fives is linked to worse physical health, mental health and behavioural outcomes. It’s also detrimental to their education, being associated with worse cognitive development, maths and vocabulary skills.

Evidently, children who face these kinds of challenges are not being set up for future success. The need for action is pressing.

So, what can be done?

Tackling this problem isn’t easy, and as experts in this area (including Trussell Trust CEO, Emma Revie) have noted, child food poverty is just one symptom of a wider problem: poverty.

But there is cause for optimism. There is strong public support for tackling this issue across the political spectrum. Labour’s 2024 General Election manifesto stated they wanted to end mass dependence on emergency food parcels, calling it a “moral scar on our society”. It also pledged to create an ambitious strategy to reduce child poverty – this was supposed to be published in the spring this year, but has now been delayed until at least the autumn. Although there have been some hiccups along the way, the rollout of free breakfast clubs in primary schools is welcome, too.

But on the current trajectory, child poverty is projected to rise by the end of this parliament. The Government must go further to follow through on their commitment – and reducing food poverty is key.

An immediate priority should be to expand access to free school meals so that all families on Universal Credit (UC) are covered. One in six households receiving UC are experiencing food insecurity, and the current income cap for free school meals excludes 1.7 million pupils in families who should be eligible. Providing these children a guaranteed meal during the school day would be a good start.

The Government should also abolish the two child limit on benefits, a policy described as ‘cruel’ by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Ending the cap could have a major impact on tackling poverty and disadvantage, ensuring families have sufficient income to meet their basic needs.

The Trussell Trust’s data paints a deeply unsettling picture of food poverty in the UK. It’s vital that we don’t normalise these numbers. If left unaddressed, we will be limiting the potential of the poorest young people across the country and inflicting long-term damage on our economy. Action on these issues is essential to realising the Government’s mission to tackle barriers to opportunity.